A group of African-American campaigners in New York is opposing the repatriation of the Benin Bronzes to Nigeria.

The group, called the Restitution Study Group, is planning to sue the Smithsonian to stop Oba Ewuare II of the Kingdom of Benin from receiving more of its collection of the looted artefacts.

The Oba has already received three Benin Bronzes from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and others from the Smithsonian, which they say was a move to “right a wrong.”

However, the Restitution Study Group argues that the bronzes were the proceeds of the royal’s ancestors selling their ancestors into slavery, and returning them would reward slavery twice.

The Benin Bronzes were taken by British colonial troops in a “punitive raid” in 1897, and there are now around 10,000 of them scattered across museums and universities in the US, UK, and Europe.

The debate surrounding their repatriation has also seen calls for the British Museum to return the Elgin Marbles to Greece.

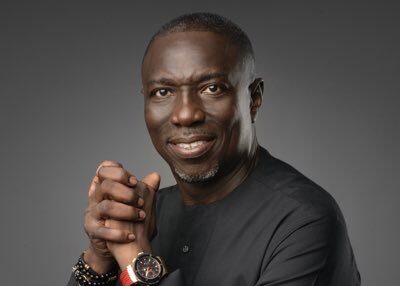

Lawyer Deadria Farmer-Paellmann, the executive director of Restitution Study Group, the non-profit trying to stop the repatriation of the Benin Bronzes, in an interview with the New York Post, said: “These are slave trade relics that are being returned to the heirs of the slave trade. They are rewarding slavery twice.”

In 2021 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, also known as the Met, agreed to send three works of art to the Nigerian National Collections: two 16th-century brass plaques created at the Court of Benin and a brass head from the 14th century.

That same year, the Met and Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments also signed a memorandum of understanding “formalizing a shared commitment to future exchanges of expertise and art.”

And last October the Smithsonian also sent 29 artefacts in its collection to Nigeria.

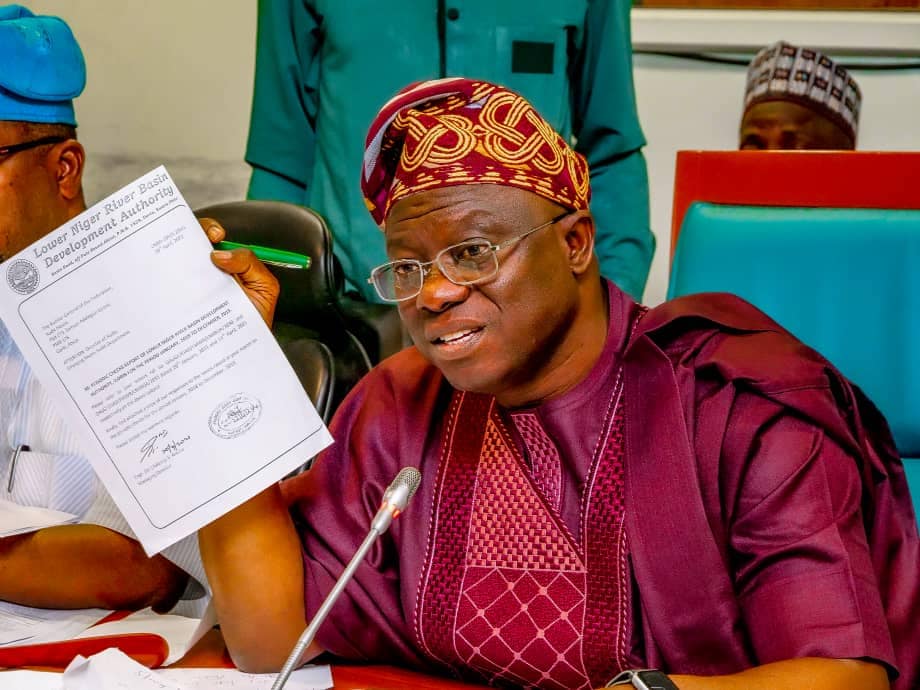

But while the government of Nigeria was the official recipient of the looted works in 2021 and 2022, last month a government gazette declared that Oba Ewuare II is “the rightful owner and custodian of the culture, heritage, and tradition of the people of Benin Kingdom.”

That means that the monarch is now on a path to a $30 billion fortune — but the move has made the idea of sending the bronzes to Nigeria much more controversial.

Farmer-Paellmann’s group sued the Smithsonian Institution in an effort to halt their repatriation plans last year, and although they lost that case, are planning to go back to court, she said.

The group says it speaks for 32 million “DNA descendants” of people sold into slavery in Nigeria and transported to the US.

Legal experts, who specialize in restitution, say that Farmer-Paellmann and her group raise some important issues.

“I think the American DNA descendants have a good moral and legal case to share the bronzes, and they are being ignored by the Nigerian and US museums,” said William Pearlstein, a New York lawyer who is an expert in art law and restitution.

Farmer-Paellmann argues that the Kingdom of Benin helped organize the Atlantic slave trade.

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, its rulers and nobility accepted brass or copper “manillas” or ingots from European slave traders in exchange for human beings. Many of the manillas were melted down to create the intricate series of metal plaques and sculptures that decorated the royal palace in Benin City until the British took them, the group says.

That makes the Oba the wrong person to get the works, according to Farmer-Paellmann in the interview with the New York Post.